This originally appeared on misteragyeman.blogspot.com on August 28, 2015.

Warning: this is a pseudo-listicle.

Recently I’ve been reading titanic writing from GQ, the NY and LA Times, Esquire, Wired; learning big new words like metastasize and scrofulous and pulchritudinous— guess which one means beautiful— but there’s some things that are best handled by Cracked journalism. I won’t rank though. Everyone’s a winner here.

Lies. Possibly civilization’s greatest tool, after coöperation. Most closets come with skeletons pre-installed. But how do we define a lie to begin with? ‘Real’ used to be a legal term. It described concreteness. Thing is, the best lies have healthier skin than most facts. Fiction becomes fact, if you work hard enough at it. In Russia, they say: if Putin lies today, it will be true tomorrow.

So for this article, let’s rate fibs by the investment of the fibber. There are cheap, reflex lies that just save trouble; those don’t count. The people I’m going to write about— their lies cost them years of their lives. Their lies cost them careers, reputations. Some dedicated their lives to the lie. They put in the effort. They deserve some credit.

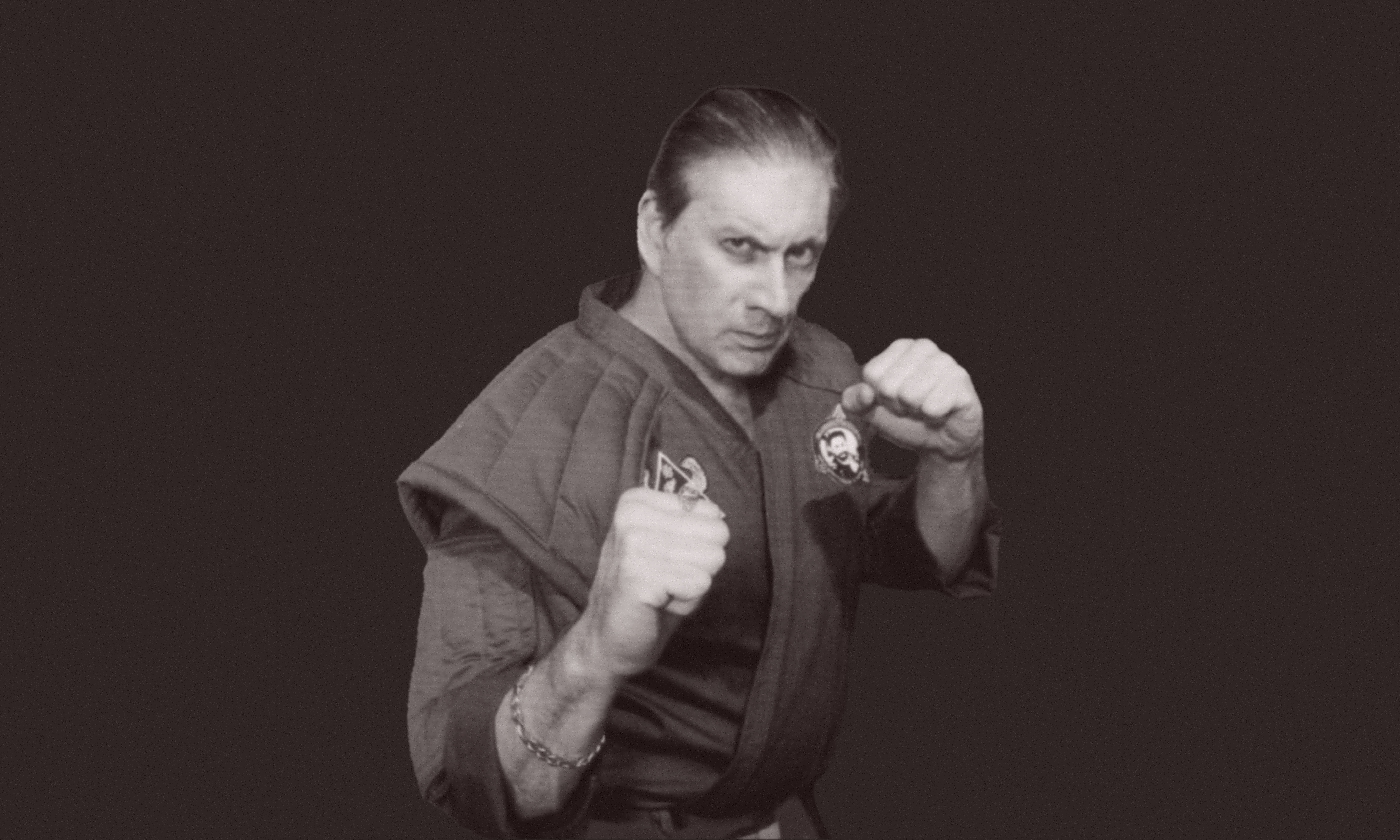

Frank Dux

Last name pronounced ‘Dukes’. This man is the inspiration for this article. Why? Because his autobiography inspired the movie ‘Bloodsport’, which gave the world Jean Claude van Damme. That’s how epic Frank Dux is; it took JVD to tell his story.

Dux is a martial artist of some standing. He has an impressive professional record, and an open-palm strike that apparently breaks bulletproof glass. There are many martial art authorities who dislike him, but nobody questions his ability to reshape a jawline with his fist. (His foot has an equally fine resume, if his fist is otherwise occupied.)

If there are concerns, they are directed at Dux’s claims. Dux says he is the heir to an ancient Ninja tribe. He says he fought in an international illegal martial arts tournament, called the Kumite. (His account of the tournament inspired the movie.) In this tournament, among other feats, Dux knocked out 56 people in a row. According to one analysis, this would imply that each match lasted less than a second. He did all this after a legendary career in both the Army and the CIA. Basically, Frank Dux is every villain’s worst nightmare, especially if they deal in child slaves. Frank Dux loves children.

The amazing thing is how believable it all is. One, Frank Dux seems capable of the physical feats, if not the 56 consecutive knockouts. Two, all the things he claims to have done wouldn’t be public knowledge. Three— why would any normal, successful martial artist make up things like this?

Turns out, many martial artists do it. It’s become a bit like fishing yarns, I guess. They kill twenty people and rip out somebody’s heart, then limp off to give the baby Lama back to the monks on the mountain. Explosions ensue, while stirring string music plays. Still, Frank Dux stands apart. Did I mention he has a box full of medals from several branches of the military? It’s like a mixed bag of sweets. Apparently they called him up one day and explained why his legendary service could never be publicly recognized. The next day, he got an envelope full of hearts and crosses. It’s like James Bond is real, and he is actually Stephen Seagal. Now If he could just stop doing all his own write-ups in the third person.

Janet Cooke (ft. Washington D.C. Authorities)

Not quite as ha-ha funny, this story.

The remarkable thing about these lies is the investment-to-profit ratio. In this way they are much like nuclear bombs, because by the time they reach critical mass, they really can’t be controlled. This lie came quite close to vaporising a lot of people in Washington.

Janet Cooke was a journalist at the Washington Post, also known as “the people who brought you ‘Watergate’ ”. In September of 1980 she wrote a startling piece entitled ‘Jimmy’s World’. The Jimmy in the story was eight years old, a crack addict from birth, hoping to make a name for himself in the heroin business someday. The story shocked people, and there was enormous public interest in Jimmy’s case, prompting the city of Washington to try to find Jimmy. Unfortunately, Jimmy was a figment of Janet’s imagination. Questions started circulating, but editor Bob Woodward of ‘Watergate’ fame went ahead and submitted the story for the Pulitzer prize. It won.

Did the city powers see this as a wake-up call? The PR department certainly did. They had tried to find Jimmy, and they couldn’t. Cooke at this point was insisting on her duty to protect her sources. What to do? Announce they’ve found Jimmy? Yes! Then they announced Jimmy was doing well in state custody. Then they announced that Jimmy had died.

Poor made-up Jimmy.

Around this time, Janet Cooke was facing a lot of questions. Her previous employers started challenging her resume claims. Then it turned out that she didn’t really have a Vassar degree. Then, under pressure, Janet Cooke confessed that she hadn’t exactly talked to a Jimmy, but she believed he was out there. I suppose it could be the Jimmy who died?

Janet Cooke resigned, and gave back the Pulitzer. (Apparently Gabriel Garcia Marquez said she deserved the Nobel Prize for Literature; the story was that heavy.) She laid low until GQ did a feature on her. She later sold the movie rights for some 1.5 million dollars. Marion Barry, mayor of Washington D.C., should really have taken something from the story. He was later convicted on drug charges, after years of parrying rumours of cocaine addiction. He survived the felony, just like he survived this massive PR disaster, and came back as mayor. Because life is wonderful.

Ferdinand Waldo Demara

You know Frank Abagnale— the guy from ‘Catch Me If You Can’? Well, if Frank ever met Ferdinand, he would have to call him ‘sir’. Because Ferdinand Demara wouldn’t be an accountant, or a pilot. He would be CEO, or head of Flight Control. He didn’t have jobs; he built careers.

At sixteen, Demara ran away to a monastery. Monasteries are a recurring theme in his story. I suppose he found them restful, when he wasn’t fibbing with all his strength and might. Anyway. From there he went to the Army. It didn’t take. He deserted under an assumed name, and tried the monasteries again. Then on to the Navy, where promotions didn’t come fast enough. (Remember: he built careers.) So he faked his own suicide. On to psychology. He taught for a bit, then he thought he’d try the hands-on approach, so he joined a psychiatric hospital. Then, having learned the business from the ground up, he went to impart some more knowledge to the young ones. Then the FBI decided to impart some knowledge to him. Turns out, you see, that the military doesn’t like people leaving without saying goodbye.

After he got out of jail, Ferdinand— ‘Fred’ to friends— studied law at night school. Then he joined another Roman Catholic order. Then he met Joseph Cyr. Maybe he just liked the name, or maybe he believed that a healthy mind belongs in a healthy body. So he mixed his medical interests with his military ones, and enlisted as Joseph Cyr, surgeon, on a warship.

Here’s where it gets fun. The Korean War was underway at this time, and Demara’s ship, the ‘HMCS Cayuga’, took on sixteen battle casualties. “Calling Joseph Cyr!” Does Freddie say “Catch me if you can”? No sir. Freddie innovates. Freddie assimilates the training and knowledge of years of medical school from a textbook, steps up and scrubs in. He cuts chests open. He digs out bullets. Does he puke? Not our Freddie. Does he repine? He saves lives.

The man didn’t lose one patient of the lot. He performed so well, newspapers picked up the story. And so it happens that Joseph Cyr, surgeon, goes to the military and asks, ‘What’s this I hear about me saving lives?’ Understandably, the military wasn’t sure what to do. Demara did enlist under a false name, with false accreditation— but he was basically a plump boxed set of ‘House, M.D’. They let him go, and didn’t press charges. They should have given him a medal, the ingrates. An envelope full! They should have built him a monastery.

Pardon me. Need to pull myself together.

We follow Fred back to his brethren of the Holy order. He founded a college for these guys, but left because they passed him over for the dean position. Also, their naming choice apparently sucked. Then came Fame, and that was the end of Ferdinand Demara. He got featured by Life magazine, after which he couldn’t even keep a job at a prison without an inmate recognizing him. His great highlight in this third stage of his life was a bit part in a film— this from a man who seems to have lived to provide John Goodman with Oscar material. Such is life.

We pass onto the final stage of Demara’s illustrious career, and what do we see? He takes a regular job. As chaplain, of course, in a hospital. What’s more, he actually earns a certificate from a Bible college. His phenomenal mind and remarkable spirit occupied itself with a regular schedule. Of course it’s nice to see him defeat his demons— if he did, that is; still, one can’t help but wonder what might have been. ‘Demara for Senator’? It seems inevitable. He had experience dealing with mad men, and his fibbing is unparalleled.

Marvin Hewitt

Marvin Hewitt happened to read the Life Magazine feature on Ferdinand Demara, and was struck by the similarities. But where Fred speculated, Marvin specialized. No hopping about for him. He knew his career path, and he stuck to it.

Marvin was one of those people who love learning so much that they can’t stand to be in school. At ten, he discovered advanced mathematics. At twelve, he was grappling with relativity. He tried to share his discovery with his teacher and class; they didn’t quite get it. At seventeen, Hewitt dropped out, whether from sheer boredom or some deeper conflict. But it was ‘au revoir’, not ‘adieu’. Marvin and the schoolroom would be seeing a lot more of each other. In the mean time, he did blue-collar work, lightened occasionally by prize-winning essays for a newspaper competition.

Then his destiny came calling, in the form of a want ad for an eighth-grade teacher. He quickly climbed from grade-school math, geography and history, on to college-level physics. Of course, in his spare time he was operating on the very frontier of theoretical physics, but you take what you get. He mailed the university of a promising young doctor of physics, got himself a transcript. and set off as Julius Ashkin. Maintaining his double life became his first priority, until even when he was mourning his father’s murder, he was avoiding journalists. He soon moved on, partly to escape detection— and partly because he wasn’t getting the pay that his bogus identity deserved. Then Julius Classic went and became famous, so Julius Deluxe moved up again, to graduate courses this time. And then again, and again– a higher promotion with every move, until he was making full professor status on the strength of good old Jules’ research and papers. All was rosy. And then Dr Julius Ashkin 1.0 wrote to Dr Julius Ashkin Beta.

The man was cool, though. He didn’t report him or anything, realizing correctly that it takes more than a name to pull off a career like that. But other reports came from other sources, and Marvin Hewitt was painfully exposed. He licked his wounds and slipped out of town. And here we are faced with a question: can a person in Marvin’s condition be expected to go straight? Several legitimate colleagues of his tried to help him get on track to do what he did for real, but he let the opportunity go past. Instead, he just switched subjects, to engineering. This time, he made up a name, so he got to publish papers of his own, way ahead of his field. Then he got caught, and back to physics, at two different schools. It’s possible he could have kept his last job if he’d passed the one student who was on to him, but no. Marvin Hewitt respected his job— he failed the sucker and left town. He would probably have applied again, but everything leaked, and his career was over.

Even when his former colleagues knew that he was an imposter, they were still shocked to learn that he wasn’t a PhD. The man loved science, and taught himself all he could. He tried to get to Einstein once what for, I do not know. I don’t doubt he would have made some corrections to the general relativity theory.

The moral of this story? Don’t flunk students.

Han van Meegeren (ft. Joseph Piller)

Han van Meegeren could have been a rock-star. For one, he fooled Hermann Goering. Any enemy of Hitler’s— that crazy dude we love to hate— is a friend and brother to all. He’d be on late-night television all the time. Plus, everybody did forgeries in the good old days. Michelangelo mocked up Greek statues all the time, with little touches of decay and erosion— sometimes, on the special request on the client. The customer gets cheap prestige, the artist gets hard cash, everybody is a winner with forgeries. Meegeren himself made a name early on with copies of Rembrandt and Vermeer. But when critics started saying he was only good for copies, he vowed to make the critics see his genius. How? He would make originals. See him now, throwing the newspaper down, pounding his fist on the table, speaking in delightful Dutchery. The Masters would live again!

After that stirring scene, we move naturally to the training montage. For years, Meegeren prepared for his masterpiece. He reproduced the old-school pigments, and got the classic brushes and canvases. He invented a process of maturing and wearing his paintings (here we get the classic test-tube scene) and immersed himself in the Old Masters. He made some trial runs. Finally he was ready. He called up his friend, and gave him a Vermeer.

“I wonder if we could have this analyzed,” we see him saying in his musical tongue. “You are acquainted with the eminent scholar, Bredius, are you not?”

Meegeren had beaten the tests, and his style was psychologically perfect— quite original, but with enough of Vermeer that the eminent scholar, Bredius, considered it to be one of the legend’s finest. Han van Meegeren could now walk into the nightclubs of which he was so fond, and make it rain. But that was secondary; the big thing was that his painting was the centerpiece in an exhibition of the old-school Masters. For pure richness, this is up there with caviar and Black Forest Gâteau.

Why didn’t the man come out at this party and do the classic ‘It Was I’? Well, the millions of guilders likely presented a compelling argument. Consider: it’s great when you’re placed in the league of Vermeer and Rembrandt, but there’s a level of appeal that you only get when you’re dead. We see this at the Oscars— play a corpse and you’re golden.

But I digress. As things unfolded, six new Vermeers were miraculously discovered in a few years’ span. Also, two unknown masterpieces from some other genius unfortunately named Hooch. (I Googled him just now, and he is rather good. Poor guy.) Meegeren started living like a boss, even in the middle of World War Two. He developed expensive tastes, and unfortunate habits. His painting and wits began to suffer, which makes it all the more incredible that his agent managed to sell a ‘Vermeer’ to a Nazi banker. That guy in turn, passed it on to Goering, who liked some art after a long day’s murder. Then the war ended, Nazis got beat, the art got recovered. (See ‘The Monuments Men’? It was in the salt mine.) The banker got questioned, and he snitched on Meegeren, who was arrested on suspicion of collaboration with Nazis.

Unfortunately, he kind of did like Nazis. Which is why he could live big during the occupation. Even signed his book for Hitler, “to my beloved Führer”.

Han van, man, you don’t make it easy to love you.

Anyway. Here, we introduce a guest star of the fraud, Joseph Piller. This guy arrested Meegeren and received his confession of forgery. (Fun fact: to prove his guilt-slash-innocence, the man had to create a new piece before experts and court witnesses.) For some reason, Piller helped Meegeren to sell the narrative of the brave artist who duped the dirty Nazis, even when the truth was coming out. The Dutch loved this angle— the world loved this angle, and so Meegeren remains ‘The Guy Who Tricked Hitler’. Awesome rep to have. Still, he was also the guy who tricked everybody else, scooping 40-plus million dollars. (‘In today’s money’, as they say.) The treason charge was dropped, but Meegeren was convicted for fraud and sentenced to jail, and his estate was sold to repay his victims. Then his health failed, and he died before his sentence began.

And after Meegeren came Meegeren Jnr., who saw fit to forge his father’s pieces.

Life.

Leave a Reply