I had plans to make a lot of music in 2018, but then my laptop’s sound card crashed, and my professional life took a detour. Still, I started learning piano and guitar, and began considering composition as separate from songwriting. Also, when I began working with a documentary production crew recently, I decided to try writing theme music for our projects.

Then, last month, with a deadline looming on the edge of my vision, I sat down behind a Mac with a MIDI keyboard. There was no conscious plan, but I suppose I had the soundtrack thing in mind. I launched Apple’s Logic DAW, found an acoustic guitar module, and began tinkering.

I’ve been noticing — by involving new motor skills, each musical instrument seems to dictate new directions. Even with years of playing the bass, the guitar still draws a different sound out of me, because of the unfamiliar tuning and plucking techniques. Because my composition process heavily depends on happy accidents, I often benefit from the relationship of body to instrument. On guitars, I hear more harmonics, and I focus on the overtones of simple chords. But I don’t know how to sustain notes correctly on the electric keyboard, so I can’t milk harmonic interactions. Instead, I focus on melodic shifts, and how to blur them. By choosing the acoustic guitar tone in Logic, I suppose I was trying to blur these two systems.

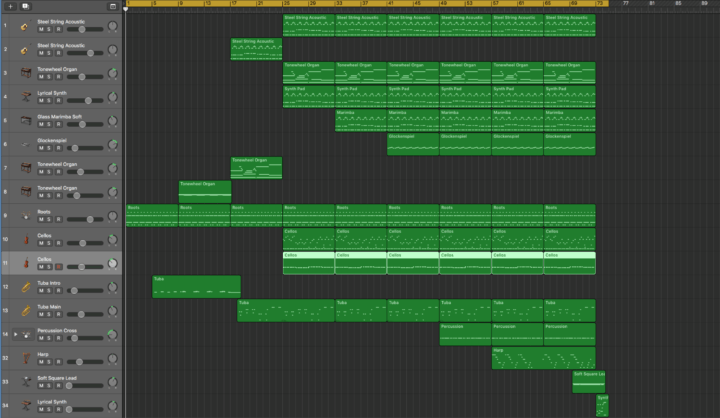

So I pressed ‘Record’, chose a plucked acoustic guitar tone, and played the first pattern that came to mind. I can only play in the key of C, and I don’t have a firm grasp on formal chord theory, so it was a simple progression. It didn’t sound much like a real guitar, so I laid a synth pad over it. The magic of digital sound modelling took the same MIDI notes and created a new texture out of them. I duplicated again and put a tone-wheel organ on, but shame compelled me to delete the old notes and play something vaguely organ-appropriate. Then I settled down to wrangle with the rhythm section.

Drums were my first joy. When I was 10, I created a drum kit with pots and pans. (Many legends started the same way, but my drumming journey stops there.) I did get into body percussion as a teen, but that only helped to mess up my limb independence. When I play keyboard drums, I seem to lose even the musicality. My first attempts on this project were pretty weird; whenever a pro drummer passed by the studio, I could feel them cringing. Instead of complementing the melodic energy, I kept muddying it up. Finally, after an hour of wrestling with the digital kits, I settled for a sparse version of one of my earlier takes.

When I started arranging the bits into a song, I noticed the many gaps in the structure. Cross-rhythms! I cried, lowering my head and pawing at the keyboard. MIDI is essentially a percussive system; you can trigger samples of rich harmonic tones if you know how to coax them out, but with attack-heavy sounds, the relationship is instinctive. So I went to town with marimbas, harps, and tambourines.

Then, as I played through the song for the last time, I realised I didn’t have any bass. I sat back down and created things that should make a bassist blush — make any musician itch, really. Then I wandered over to the brass section, casually tried out the trombone voice, and ended up with the strongest bit of the project.

This song was the simplest composition of the lot, and also the warmest song. Music often works like that; maybe all art follows the same rule. When artists enter the experimental state of mind, the intent and the process are often more satisfying than the result. That is not to say that pop art is always beautiful, but at least it keeps the audience involved. The problem usually comes when pop artists misjudge the audience, or indulge their low expectations and sentiments. (I should explain: my definition of pop art goes beyond genre. I see artists of the people in every category, from Oscar Peterson to Pete Seeger to Philip Glass — including M.C. Escher and Terry Pratchett.)

I try to keep the people in mind when I create, but there are lapses. It’s easiest when I find something special with no conscious effort; that humbles me, and makes me eager to share the experience with other people. But sometimes my creation feels more precious because it was difficult; the joy was in the journey, and the main emotion at the end is pride. When a song happens this way, it feels like a trophy. Wouldn’t it be better if I treated it as such, and kept it in a cabinet for my private ego-tripping?

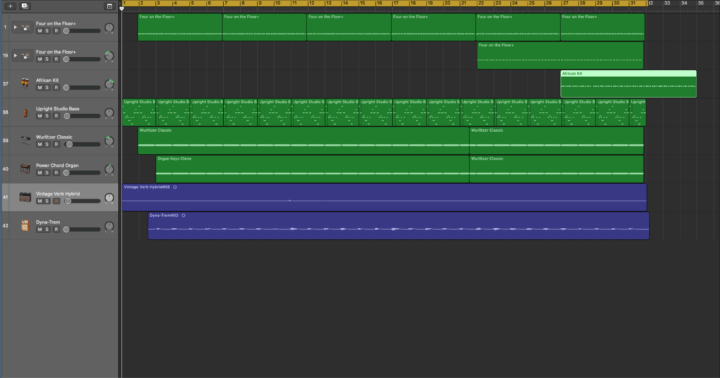

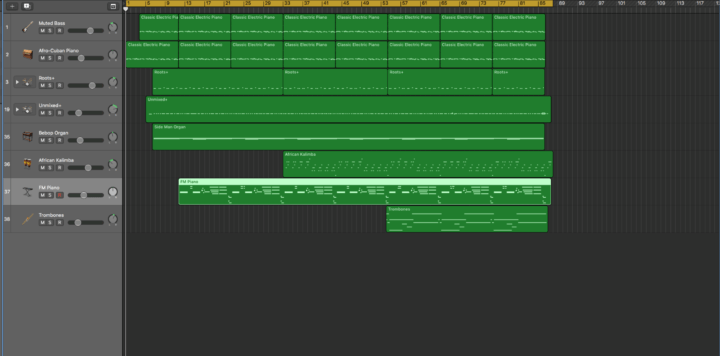

When I recorded that trombone and even the dynamics came out right on the second try — when I played the song through and felt it click — I felt a strong buzz of the first description. On the second song, as I felt the odd time signature soften and rumple under my speculative guitar line, I felt a mixture of both joy, and pride. On the third song, when I finished recording the top-end piano (done at 92 BPM, before resetting the project to 115 BPM), I felt a rush of pure ownership as I realized that my fusion-jazz swindle was paying off. I think if we are honest as artists, there is little doubt about where the audience fits into the picture.

Anyway. The project was fruitful in some ways, and unsuccessful in others. I chose untreated samples and tones with wide harmonic ranges, so that I could learn how to mix things with frequency equalization. In the end I just stuck to levelling, slapping mixing pre-sets on the master tracks. I never quite broke out of the MIDI-block trap, so the tracks don’t have any real narrative texture to them. The main way I tried to fight that was by laying off the quantization when I could afford to. Also, I tried to overlap my measures; 4‑beat measure for drums, 8‑beat for bass. I don’t know if that counts as a principle of counterpoint, but that is what I was aiming for. (I discovered this TED-Ed video after I finished, which explains cross-rhythms with a circular loop system; it shares a lot of features with my mental model, but does it better.)

Probably the first track was the best candidate for a real story, because I actually understood that progression. On Track 2, I had trouble even finding the time signature for my initial bass-line. Track Three was full of Hail Mary passes and awkward cover-ups. The most important diagnosis: my keyboard play needs work, both in technique and chord theory. Secondly, I haven’t really started production yet. I was too lazy to fix the many mistimed phrases, and I didn’t think through some of the cross-rhythm patterns. But it’s a start; and all three songs are interesting enough that I can return to them in the future.

The MIDI Project: Listen

(Right-click any track to download)